Editors: Victoria Zambello, Holly Pashley, Aoife Parr

Kace Boland is a volleyball player at Georgetown University. When she arrived at Georgetown for her freshman year in the fall of 2019, she was extremely focused on bettering her athletic performance. She practiced while the team was out on off days, did extra workouts in the late hours of the night, and controlled her diet immensely. Kace’s success with that routine did not last long, as she began to be anxious and exhausted, completely unable to perform on the court and in the classroom. As things worsened, she decided to pursue psychiatric help, and her treatment team ordered an end to her first season of volleyball. Kace wants to share her story, including what she has learned and continues to learn every day.

Q&A

Q: When did you decide you wanted to participate in college athletics? What factors contributed to your decision?

Kace Boland: I have wanted to be a Division I athlete since I was a little girl. I played competitive soccer throughout my childhood and there was never any question as to whether or not I’d pursue it at the collegiate level. I have a fairly obsessive personality; I have a tendency, for better or worse, to take my passions on as my entire identity. After losing soccer to a mild traumatic brain injury when I was 13, I picked up volleyball during my sophomore year of high school. I knew the odds were stacked against me (considering my medical history, timeline, and egregious lack of coordination), but it wasn’t long before I had set my sights on a collegiate volleyball career. I wouldn’t call it a decision. There was no distinct, epiphanic moment; I just knew from my first club practice that my heart now belonged to volleyball, the joy it brought me was unmatched, and I was going to play at the highest level possible for as long as I could.

Q: Explain the experiences that led you to redshirt in order to recover and work on your mental health.

I began struggling with disordered eating habits when I was 12 years old. It started the way it does for many young athletes — as an innocent attempt to optimize my nutrition and body composition to excel in my sport. Unfortunately, as I mentioned before, I have a natural tendency toward obsession. I’m goal-oriented, perfectionistic, and I crave control. As my body began to change, I developed somewhat of an addiction to the “progress” I was making. I delved deeper into my eating disorder (at the expense of nearly every other facet of my life) chasing the high of control. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I was becoming an object lesson in one of the most valuable pieces of advice I received in treatment: “The more you attempt to control your body, the more it will control you.”

When I reported for my first collegiate preseason, I thought the bulk of my struggle was behind me. I was meticulously tracking every calorie I consumed and expended to ensure that I was healthy enough to play. I thought that being weight restored meant I wasn’t sick anymore. In reality, I was the sickest I had ever been. Combined with the demands of Division I athletics, my additional self-imposed training routine, a rigorous pre-med course load, and a handful of comorbid mental health conditions I had yet to address, my eating disorder swallowed me whole. I was so far gone that I couldn’t even see it. I attributed my rapid decline in performance to a lack of discipline and used that to justify becoming progressively more rigid and less compassionate with myself.

Eventually, taking medical leave was no longer an option. I developed a stress-induced headache condition that made school nearly impossible. I was throwing up and passing out constantly because of the pain. I also began to dissociate for days on end, training absurd hours in a daze with no acknowledgment of the damage I was doing to my body. Georgetown Athletics ordered that I undergo a battery of neuropsychological testing to assess me for long-term concussion complications. I couldn’t even remember my own home address at the appointment. The results were terrifyingly clear — I was not dealing with post-concussion syndrome. I was just extraordinarily stressed, anxious, depressed, malnourished, traumatized, and in pain. My brain was shutting down to protect me from the way I was feeling. Volleyball was off the table. As soon as I lost the accountability that volleyball provided, I began restricting again. It didn’t matter that I now had an excellent treatment staff, medication, or my entire Hoya Volleyball family cheering me on. I was too medically compromised to remain at Georgetown. I spent the bulk of May through October receiving inpatient treatment halfway across the country. Although it was inarguably one of the most arduous experiences of my life, I am immensely grateful for the privilege and opportunity to heal under such exceptional care. I have since fully surrendered to the recovery process and am slowly rebuilding all that I lost to my eating disorder.

Eventually, taking medical leave was no longer an option. I developed a stress-induced headache condition that made school nearly impossible. I was throwing up and passing out constantly because of the pain. I also began to dissociate for days on end, training absurd hours in a daze with no acknowledgment of the damage I was doing to my body.

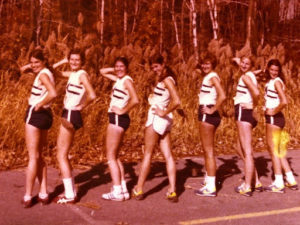

Kace Boland, Volleyball Athlete - Georgetown University #11

Q: What is the most impactful piece of advice you have been given in this journey, and how did it impact you?

I don’t know that I can pick a single most impactful sentiment! One idea that I find myself revisiting frequently is that “No one wins an eating disorder”. It isn’t anything profound, and it may seem comically obvious, but logic goes out the window in the depths of an eating disorder. There is a reason you never hear stories of someone developing an eating disorder, unhealthily manipulating their bodies to whatever shape they desire, and then deciding, “Yep! This is enough!” and going on to function healthily in their daily lives. It just doesn’t happen. Oddly enough, however, it’s a delusion in which millions of people destroy their lives every day. I restricted myself in hopes that I would one day be lean enough to accept my body and feel okay again. Every time I hit a weight loss goal, I would immediately decide that it wasn’t enough. No figure or number on the scale ever brought me the peace I sought because my body was never the problem. My obsession with my body was a manifestation and symptom of other struggles, and engaging in disordered behaviors was only exacerbating my pain.

Q: What are your plans for the future?

Beyond my aforementioned plans for my return to Georgetown, I hope to attend medical school and specialize in either psychiatry or family medicine. With respect to the likelihood that those aspirations will change, my ultimate goal is to take on a role similar to that which my doctors, dietitians, athletic trainers, and therapists played in my own story. My outpatient treatment team saved my life. I didn’t trust them because they were exceptionally talented medical professionals (as I probably should have), but because they made it exceedingly clear that they truly cared about me. They refused to let me bear the weight of my life’s most trying chapter alone. I’ve wanted to be a physician for as long as I can remember, but I have never been more excited about a career in medicine than I am right now. They’ve set a dauntingly high bar that I can’t wait to chase.