Holly Crane is a personal trainer, educator, and consultant with a passion for making the fitness industry a better place.

A few weeks ago, Katie Loftus sat down with Holly to discuss weight room gender dynamics, beauty standards in the fitness industry, and what inclusive fitness looks like.

To learn more about Holly Crane, you can visit her website.

What sparked your interest in fitness?

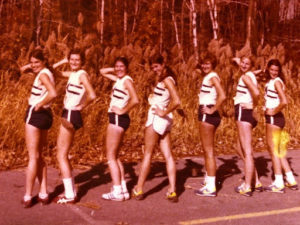

I discovered fitness after being an athlete for most of my life. My first sport was cross-country skiing, of all things. I also played lacrosse, soccer, and I did some alpine racing in high school. My first experience in a gym (other than the few times I would use the treadmill in college) came after graduation, when I moved to NYC to pursue an acting career. I got a day job as a front desk associate at an Equinox in Manhattan. I started working out with various trainers at the gym and I quickly fell in love with the barbell. I loved feeling strong and watching myself get stronger and I wanted to share that with others. I decided to become a personal trainer and the rest is, as they say, history. Training was so fulfilling to me that I ended up quitting acting. I’ve now been training for over 8 years.

Can you give our readers a brief overview of your experiences in fitness since?

In addition to my being a trainer, I am also a certified strength and conditioning coach and I’ve spent time working with both high school and collegiate athletes. I also spent about two years as a fitness manager, where my job was managing a team and teaching them how to be more effective trainers. I’m also a competitive weightlifter (that’s the sport where you do clean & jerks and snatches), so I’m fully entrenched in the weird and nerdy world of strength sports. I’ve just recently started my own business, which is part personal training and part consulting within the fitness and athletic industries. As a trainer, my specialty is pre/post natal and pelvic health. As a consultant, I work with industry professionals to create accountable and responsible communities and teams.

Your graduate research focused on gendered fitness spaces, such as gyms. Can you tell us what your key findings were?

In 2017, I received my Masters of Science in Kinesiology from the University of Minnesota. My thesis was called “A Psychosocial Examination of Women’s Relationship to Strength Training and the Weight Room”. The purpose of my research was to examine the factors associated with women’s low use of weight rooms by conducting a survey of female users at the university fitness center. Consistent with previous research on body image and women in gyms, I found that women in the gym used cardio machines more than free weights and were more likely to exercise in places where more women were present. From a body image and anxiety perspective, the women I surveyed were also moderately high on a number of scales related to social anxiety, body image distress, and gender role stress.

I also analyzed the type of equipment and the type of spaces that women used in the gym. The data I collected suggests that some women consider lifting weights to be a masculine activity, which makes them less likely to participate. It also indicates women with less stress about traditional gender roles may perceive fewer barriers to exercising in male dominant spaces.

Overall, my research results suggest the following. If women consider free weights to be masculine, they are less likely to use them. Women engage in particular types of exercise based on their relationships to gender and to what they perceive as the ideal body type. Women’s self-perception and relationship to perceived gender roles may dictate their use of mix-gender gym environments.

In other words, sociocultural gender norms play an important role in the exercise behavior of women.

How is the gender binary at work in gyms and why is this important for womxn athletes?

The gender binary is the cultural assumption that all humans fit into one of two distinct, oppositional, and biologically determined categories: “female” or “male.” The reality is that gender is a construct imposed by society rather than the innate or biological characteristics of a person. Gender is one’s innermost concept of self. It is fluid and not confined to a binary. However, the concept of the gender binary has been used as a social organizing principle for hundreds of years. This is particularly true in the West, where 19th century colonial scientists began using pseudo-scientific methods to establish bodily differences between two sexes.

A long-standing legacy of this categorization is the idea that men are physically superior to women. Which brings us to sports and fitness, where the use of gender as an organizing tool is particularly notable. Children are separated into single-sex teams as early as the age of 5. America’s most popular sport doesn’t have a comparable league for women. Far more men use the weight rooms in most gyms than women do. A strong and muscular body is associated with masculinity, while a thin and toned body is associated with femininity. These assumptions are all ways in which the gender binary is at work in fitness spaces. One of the most palpable effects of the gender binary in the gym is the feeling of being scrutinized. Chances are, if you do not look or act like someone who “should” be lifting weights (ie: anyone who is not a cis-het able-bodied muscular man), then you’ve experienced the sinking feeling that you do NOT belong in the weight room. This feeling might manifest itself as the fear that you have no idea what you’re doing, or the sense that everyone is watching you, or the compulsive need to hide yourself in some far corner of the space. This feeling is the direct result of a system defined by the gender binary. A system in which masculinity and femininity are narrowly defined, biologically determined, and mutually exclusive. This system is detrimental to all of us, and yet many of us cling to it like our lives depend on it.

Athletic performances in womxn’s sports are constantly evaluated as lesser-than relative to those in men’s sports. Where does this belief come from and does it have any merit?

Basically no. There is no merit behind the belief that women are less strong, less athletic, less anything than men. Speaking from a strength perspective, here is a quote from the National Strength and Conditioning Association: “When strength is expressed relative to muscle cross-sectional area, no significant difference exists between sexes, which indicates that muscle quality (peak force per cross-sectional area) is not sex specific”. (Boechle, R.T., & Early, R.W. (Eds.). (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. NSCA).

In other words, when we control for the relative size of muscle fibers in men and women, there is no difference between the sexes. Despite this scientific truth, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that contradicts it. The most frequently cited examples are usually in the worlds of strength or speed. Ie: the strongest man in the world outlifts the strongest woman in the world, even when you control for size. Ditto for the fastest man in the world. The issue here is that we are assuming strength differences are purely a function of physiology. We are using the construct of a gender binary to explain the reality that we observe. “Ah yes, this MUST be because women are inherently weaker.” But this is rather like putting the cart before the horse. In actuality, there are many other factors at work to determine someone’s ability, strength or speed. Factors such as cultural norms and social conditioning. Boys are introduced to weight training at a much younger age than girls. Magazines, tv shows, and a variety of other messaging teach boys that size and strength are attributes they should aspire to. Little girls? Not so much. Athletes do not develop in vacuums. They are as susceptible to culture and society as anyone else. We cannot possibly compare the experience and abilities of male and female athletes on physiology alone.

So why do people continually make this argument? Because it is “proof” of the gender binary. Because it upholds the status quo. Because, at its worst, this argument is a tool to remind women that they do not belong.

For more reading on this specific topic, here is an article I wrote for the Women’s Strength Coalition a few years ago. (*Note: in the article, I define PCOS as a disorder that only affects women. That is incorrect. What I should have said is that it affects people with ovaries).

How do gendered expectations about beauty affect the womxn you train? What can college athletes do to rewire these expectations?

Gendered expectations of beauty are another way that the gender binary is upheld in fitness and athletic spaces. In many ways, fitness is the pursuit of the ideal body. This can be aesthetic or performance-based and I would argue that the definition is shifting. But, historically, fitness has been about changing your body to be something more ideal. So right off the bat, we are dealing with a gendered concept. What is the ideal body? Well, if an alien came to planet Earth and looked at Instagram long enough, they would determine that the ideal body is thin, able-bodied, cis, and white. They would also learn that the ideal female body is quite different from the ideal male body. One is small and graceful. The other is muscular and powerful. In fact, muscularity is a key way to maintain visible gender differences. This puts women athletes in a very tricky spot. How do you maintain your femininity when attributes of your sport are perceived as masculine? This is especially difficult for athletes who play sports that yield a more muscular body (rowing, weightlifting, throwing sports, sprinting, etc). In terms of rewiring the expectations we have for how certain bodies should look – I would encourage you to curate your social media feed! Expose yourself to accounts that reflect the vast and beautiful array of human bodies! It’s a good reminder that there is absolutely nothing inherently gendered about clothes, makeup, muscles, beauty, sports, or anything at all. Expressing your gender is a deeply personal choice and you are the only person who can decide what is right for you. Here are a couple of Instagram accounts that may help disrupt the narrative that femininity is something that can be universally defined.

-Caster Semenya: @castersemenya800m

-Sarah Robles: @roblympian

-Jessamyn Stanley: @mynameisjessamyn

-Janae Marie: @janaemariekroc

How can we, as womxn athletes, make training spaces more inclusive?

I think that one of the most important things we can do to make training spaces more inclusive is to be aware of the ways they are not. And not just for ourselves! It’s helpful to remember that women are not the only people who are made to feel like intruders in fitness and athletic spaces. Trans and nonbinary folks face many obstacles, as do people of color and folks with disabilities. Think about what the locker room situation is like where you train – it is trans and nonbinary inclusive? The next time you enter your gym, notice if the entrance is accessible or not. Take the time to research the administrative side of the training space or gym. Who are the coaches or owners? Who is represented in the marketing material? Once you have an idea of how your training space or gym currently operates, then you can start to think about how you can contribute to change. If you are a paying member at a gym or training space, consider putting your money elsewhere if that space does not have inclusive values. If you notice a lack of diversity within marketing material, write a letter to management. Use your voice and your wallet! Many of you likely train in university or collegiate settings. In this case, developing workshops, group training and/or specific training times for under-represented groups of people can be a great tool to make training spaces more accessible. These can include group workouts for trans and nonbinary athletes or intro training sessions for novice lifters, among many other options. Create positive spaces for folks who typically do not feel welcome in gym environments.

And finally, remember that words and language have power. Instead of calling the 35lb barbell the “women’s bar”, just call it what it is! The 35lb or 15kg bar. No more girl push-ups, either. We call those modified push-ups instead. When you introduce yourself to new folks at the gym, include your pronouns. Make it a habit of asking people what their pronouns are, as well. If you hear someone make a joke or remark that is insensitive or offensive, speak up. Words like “b*tch” and “p*ssy” are used constantly in weight rooms. If you say things like “don’t be a b*tch!” in an athletic context, begin to remove that phrase from your vocabulary. And call out others who use those words. Systemic change is crucial to making gym and fitness spaces welcoming and inclusive, but daily actions like the ones above can make an immediate difference, as well.