Many retired athletes struggle with their mental health after the days of competition are gone. This is the story of a former college soccer player, Sarah Brink, and her experience with post-college grief.

“The first sign that I was not fine came as I stood in line at Trader Joes one afternoon, the first September following my graduation from college.”

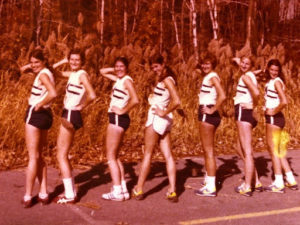

Despite the obviousness of it now, I was not okay during this first fall post-graduation, but I struggled to admit it to myself. I had spent my youth and teenage years grappling with severe anxiety, at times unable to even stay home alone for just 15 minutes. My only respite was being out on the field or on a basketball court, being part of a team. It felt like the only extended period of time where I saw myself as “normal”, existing with little to no panic, intrusive thoughts, or an impending sense of doom. By the time I got to college, my anxiety began to improve, in contexts even outside of sport. Through therapy, I had gained a toolbox of anxiety coping strategies, and I was engaging more with the things that scared me most. I graduated from college feeling confident in who I was and grateful for everything being part of a team had given me. I graduated feeling fine, and I developed a narrative of needing to stay fine. I put on a smile, tried to engage in my graduate classes, tried to be social, tried to appear like I was not spending every second wishing I could go back. Spending every second wishing for that guaranteed respite from anxiety. In my head, I was supposed to be moving forward from my anxiety, not backwards. I had come so far, therapy was a thing of the past, not something I needed as a “mature” 22-year-old. But I was drowning under the weight of trying to seem fine. Without the feeling of being part of a team, not only did I feel as though I was losing my ability to cope with my anxiety, but I was losing pieces of who I was.

“By December, I had spent four months barreling forward, trying to ignore these intense feelings of uncertainly and the bubbling anxiety.”

Despite my shame, I found a new therapist and began seeing her regularly. I connected with her immediately as she validated the feelings I was having – “well of course you don’t feel okay, there are so many changes that have taken place!”. In our first session, she offered up an emotion to describe how I was feeling that nearly knocked me backwards. Grief. It seems so obvious now, but at 23, I had reserved that emotion for a select number of incidents. Death, serious illness, heartbreak. Simply graduating from college did not make the list. But she was right. As I described the joys of being part of my college soccer team, the friends I had made, the memories I had collected, the person I had become – I was describing a time in my life I was never going to get back. I was describing an identity I had fit myself into that no longer existed. It was an identity that didn’t make sense in my world after college. Instead of allowing myself to grieve my time in college and my former identity, I wished and wished that I could just go back in time. I had not shown up for my grief in the way my body and my mind desperately needed it to, and I had confused my identity for my self-worth, for my character. And by not showing up for my grief, I couldn’t show up for my anxiety either.

“The college sports experience and path following graduation is different for everyone.”