Written by Margaret Cirino.

When the coach of the USC Women’s Rowing team, a D1 collegiate sports team, approached me and told me that I would make a great rower based on my build and whatever other combination of factors goes into such a split judgement, I thought why not, and signed up for tryouts. I had never felt proud of my athletic accomplishments and wanted to change that.

Rowing is a grueling sport. It’s one of those things in life where your input directly correlates to your output: there’s no magic formula that will help you succeed. You just do it, again and again, “becoming friends with the pain” (as my coach would say). And then maybe you’ll get faster.

The results are not immediate, either. I learned within the first few months that I would not pick this sport up naturally, and there were days I left practice in tears as I tried to understand the “boat feel” that my more experienced teammates seemed to intuitively pick up on.

But the true difficulties of rowing, a sport known for its extreme time commitment and draining physical and mental barriers, lied for me with its perception. When I announced to my freshman year roommates that I would become a rower, their jaws slackened. “You’re gonna get so skinny,” one of my friends whispered.

What I didn’t know at the time is that the “female athlete body” is not a catchall term. We all have an internal image of what a female athlete should look like, and this image is flawed. I didn’t realize that all sports would not produce the toned tennis bodies I had grown up around. I would be in for a rude awakening.

Rowers tend to be built muscularly, and rowers tend to be tall. But I know plenty of rowers who are shorter and plenty of rowers who are slimmer, and they’re fast too. The truth is that there is no one rower body, just as there is no one tennis body or track body. Training affects each body differently and all of these forms are valid.

After months of training, I did not get skinny as my one friend had predicted. Instead, I gained twenty pounds in one year. I had surpassed that mysterious milestone of the “Freshman 15,” that cultural mythos that girls much younger than me know about. In reality, this media myth is scientifically unsubstantiated. Freshmen only average an extra 2.5 to 6 pounds, as it turns out.

Yet I had surpassed this milestone with flying colors, adding an additional 5 pounds on top of the 15 that I had been warned of before college.

I never dropped the “fat” portion, either. I just grew. I bulked, broadened, stretched beyond my clothes and quickly required a new wardrobe of shorts and pants several sizes larger than they had previously been. When you work so hard for your body and it’s not praised or validated by the people around you, the wind gets knocked out of your sails. The feeling that your lifting routine works against you, not for you, is one more mental obstacle you have to overcome to perform and train to the best of your ability.

A Problem of Perception

This narrow mental image is not one that fades in the world of elite sports. It only distills, more concentrated on a global stage. I think about the sport of tennis, my high school sport, as the clearest example. There often seem to be two different yet parallel narratives in women’s tennis. We have Serena Williams, the seminal tennis icon. And then we have the rest of elite women’s tennis. Williams is known for her mold-breaking muscular build and has talked often about the long road to self-acceptance. “You really have to learn to accept who you are and love who you are. I’m really happy with my body type, and I’m really proud of it,” Williams stated for a New York Times article covering the body-acceptance movement within tennis. Her competitors often feel differently and shy away from emulating her strong frame. In the same article, Maria Sharapova, a slim Russian tennis player, said she still wished to be thinner. “I always want to be skinnier with less cellulite; I think that’s every girl’s wish.”

If elite-level athletes still grapple with these issues of perception, and even still conflate appearance with performance, it should be no surprise that athletes at the collegiate, high school, and youth levels wrestle with the same issues.

Embrace your muscles. Embrace your fat, too.

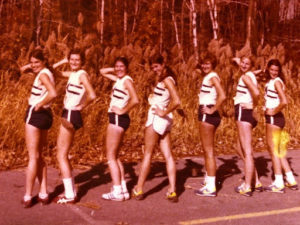

When we talk about the body acceptance movement, we talk of broadening the “list of acceptable bodies.” But we don’t acknowledge that sometimes bodies are not made to exist on a list, constrained by nouns and objects that don’t capture their capabilities. Not a single girl on my team has the same body. We all have fat hiding in different places, and all of our bodies allow us to compete and train at a high level.

Before I made the decision to take my last semester of rowing off, I surveyed my teammates on their relationships to rowing. Almost every rower describes his or her relationship to the sport as a love/hate. Sometimes the love is stronger, and sometimes the hate is stronger. When the hate begins to overpower the love, practice transitions from “hard” to “unbearable.” Every athlete enters a stage like this at some point. It gets difficult to see the “why,” and it gets difficult to feel that love that was once felt.

There are things we learn about ourselves when we put our minds and bodies through these trials. We learn to reframe our identities and our relationships with ourselves. After years of constant exhaustion, stress, and injuries, how could I ever be mean to my body? How could I ever take it for granted? And after rare adrenaline-fueled moments, of hitting the PR on my 2k, of flying, I mean flying across the finish line in a boat with eight other girls supporting me, with grace and strength simultaneously, how could my goals for my body ever be limited to appearance? It’s okay if you have muscle, it’s okay if you have fat, and it’s okay to demand more from your body. In fact, I encourage you to.

Sources

Khazan, Olga. “The Origin of the ‘Freshman 15’ Myth.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company,

6 Sept. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/the-freshman-15-is-a-myth/379587/.

Rothenberg, Ben. “Tennis’s Top Women Balance Body Image With Ambition.” The New

York Times, The New York Times, 10 July 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/07/11/sports/tennis/tenniss-top-women-balance-body-image-with-quest-for-success.html.

For more inspiration:

https://viragoproject.org/lifting-up-womxn-the-feminism-of-weightlifting/

https://viragoproject.org/public-eating-fueling-your-body-without-feeling-shame/